Siya Khumalo On His Very ‘Queer Book of Revelation’

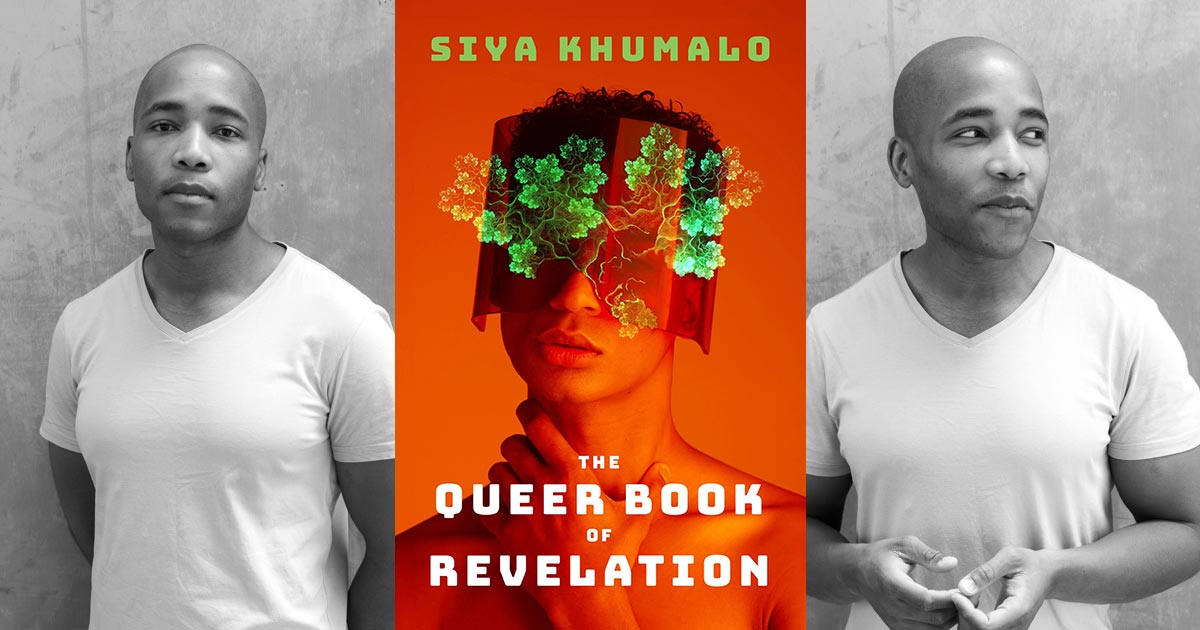

Siya Khumalo is one of the most compelling and influential queer voices in South Africa (Photos: Dirk Skiba)

Prominent author, columnist, political analyst and former pageant queen (more on that later) Siya Khumalo is launching his debut novel, The Queer Book of Revelation. It’s a bold leap into the science-fiction genre, set in a tech-dominated future.

The book follows John, who works for a regime called The Federation, which enforces emotion suppression and AI control. His life takes a dramatic turn when he’s tasked with infiltrating a colony resisting AI influence.

There, he meets Joshua, and their forbidden connection sparks a crisis of loyalty. To make things more complicated, time travellers from the future approach John, urging him to help thwart the technological tyranny threatening the world.

The Durban-born Khumalo has earned his reputation for thought-provoking commentary on religion, politics, sex, and technology, with his work appearing on platforms like Daily Maverick, News24, and MambaOnline.

His first book, the autobiographical and courageous You Have to Be Gay to Know God, was long-listed for the Alan Paton Prize, shortlisted for a University of Johannesburg book prize, and honoured with the Desmond Tutu-Gerrit Brand Prize.

And, adding a splash of glamour to his impressive résumé, he was a runner-up in the 2015 Mr Gay South Africa pageant and later represented Zambia in Mr Gay World (thanks to his part-Zambian heritage).

All in all, Khumalo stands out as one of the most compelling and influential queer voices in South Africa. We sent him a set of questions about The Queer Book of Revelation, and true to form, he responded with several hundred insightful words covering not just his novel, but also soul music, Donald Trump, the essence of humanity, and much more.

Why the move to fiction — what was the appeal?

The material in The Queer Book of Revelation was initially pitched to the publisher as a non-fiction work. The publisher suggested I turn it into a science fiction story. I’d always had three rules: I’ll never write fiction, I’ll never write science fiction, and I’ll never write science fiction with time travellers. I think I was hiding from the sheer loopiness that makes up my thought processes — I was holding back. I eventually broke all three rules!

Did writing fiction come relatively easily, or was it an entirely different experience?

I’ve always found fiction really challenging. While I do like describing sights, senses, sounds and so on, I prefer starting with real-life references and experiences.

“What would happen if someone rewrote the New Testament as science fiction?”

Was there anything that you found particularly challenging or surprising?

I struggle with structure. That’s a problem I have in any genre.

Problems specific to fiction: I discovered that characters don’t cooperate. They aren’t supposed to cooperate. They have their own agendas because they’re real, in some sense. They have to be if we have any shot at writing them with any sense of believability. This is why I don’t trust character profiles, or writers who are wholly in control of their writing processes.

Real people are coherent but they aren’t consistent. If they were consistent, we wouldn’t have an accountant going on a vigilante killing spree or struggling with an urge to embezzle company funds.

Stories happen because people snap out of character. I want to find the thing that snapped them.

Speaking of believability: What makes nonfiction easier is that I can point at a thing that happened and say, “We agree that happened, right?” I’m not asking anyone to suspend disbelief. Once we’ve agreed about the facts, the juice is in the interpretation of the facts. That’s just easier than making up a scenario but you’re always wondering, “What if the reader rejects this scene?” and you’re held back by performance anxiety.

Is this a book for sci-fi fans?

I see sci-fi as a way to reframe commentary on current events, to extrapolate on real-world power dynamics. I don’t follow sci-fi for its own sake. I hope to be forgiven for being an interloper in the genre.

I write about religion, politics, sex and technology because they’re the modalities of power. I see mythology as a form of religious confession. When people write stories about gods on power trips, they’re describing how they understand the human condition in relation to power, or how they would behave if they had godlike powers. Insecure people use power to strip others of the security they lack in themselves, and technology can take that process to unimaginable places. So the cruel and capricious gods who toy with human beings are our tech company CEOs and politicians.

In the words of Arthur C. Clarke, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” and in the hands of an insecure power-hungry person, it’s indistinguishable from sorcery, or genocidal warfare, or nonconsensual surveillance/spyware.

This book is for people who want to explore this collision of tech, politics, culture wars and such that we’re living through. That could overlap with a love of sci-fi.

What was the genesis of the story of The Queer Book of Revelation?

At the end of an interview about You Have To Be Gay To Know God, the late Eusebius Mckaiser asked me whether I’d embraced the Gospel of Richard Dawkins, aka atheism. I nearly spat out the words, “My next book is about why I haven’t” and that’s when I realised I had something to say on this topic. I didn’t have a next book in mind until I thought those words.

If I were to write that book now, it would use as its test case the fact that the tech billionaire backers of Donald Trump/J.D. Vance (companies and business leaders that used to back the progressive left) are mostly religious amphibians that straddle white supremacist Christianity and atheism insofar as either belief allows them to maintain the status quo handed down by the history of religion and colonialism.

They’re developing ideologies built bottom-up from computing language, and at the top they’re sounding identical to ancient European theological and metaphysical language. History repeats itself. Where the tech company owners themselves are firmly atheist or theistic, their fans span the religious spectrum but fundamentally have the same spiritual worldview that they have, despite the religious labels. This is to say, atheism can continue the work done by colonial religion.

“How is our making AI in our image different from the idea of God making us in their image?”

AI is already infiltrating so many aspects of our lives, even if we’re not always aware of it. What’s your take on AI, and what role does it play in the book?

Slave traders once told a religious story about black people to justify enslaving them: “They don’t have souls or feel pain the way other types of humans do.” It was partly in response to this idea that “soul music” was invented — to make listeners recognise that members of the black community were experiencing oppression and exploitation as any human being would.

This legacy of dehumanisation lingers in the way women’s medical issues are underfunded and women are expected to endure pains and inconveniences that, if faced by men, would trigger avalanches of scientific research and progress in medicine.

From a young age, children develop a Theory of Mind, which is also the name for a branch of cognitive science that investigates how we ascribe mental states to other persons and how we use the states to explain and predict the actions of those other persons. This is related to empathy.

One of the questions I’ve wondered is, what stories do we tell ourselves to justify switching our empathy off? To exploit others? And what stories can be programmed into machines, so they trick us into turning that empathy on, to manipulate us and draw us into scams? Can robots be programmed to work humans like robots?

AI is going to test the limits of our knowledge — our faith, that is our ability to ascribe states of being where we don’t have direct evidence. In the words of historian Professor Yuval Noah Harari, AI will “hack” human consciousness.

If we can disbelieve in the sentience and humanity of people who are different from ourselves, we can believe in the humanity of something that’s learning to pretend to be similar to us. So in the novel we have people being turned into zombies and robots as an elliptical comment on how exploitative systems work to dehumanise people. We become the robots of those man-made systems.

I noticed the religious element in the title. To what extent does your interest in deconstructing or reassessing interreligious or biblical matters and dogma play a role in the book?

To the fullest possible extent!

For a long time, theology was a discipline for ostensibly celibate men in frumpy robes, but technology will make many theological questions more relevant than we anticipated. We generally throw these questions into “the ethics of such-and-such a technology”, and we leave it to the Pope to address world leaders about that at G7 summits, but really I think it (along with climate change and economic instability) will affect us on the ground far more than it’ll affect powerful politicians with private jets.

As technology becomes more noetic (that is, related to mental activity or intellect — think Artificial Intelligence) it raises questions about that weird space where the phenomenal (things that can be detected by the senses, not just “phenomenal” as in “that was a phenomenal shag”, though it can mean that too) meets the noumenal (that is, something real that isn’t detectable by the senses).

This is where you get questions like “What is mind?”, and, “What happens if the algorithm figures out what makes my mind tick?” Who has power over me? What are they doing with the real estate between my ears?” For me, these are deeply religious questions, for religion is programming. The etymology of “religion” is “to bind”, the way your ligaments tie your body together.

I’ve long wondered, “What would happen if someone rewrote the New Testament as science fiction?” and, “How’s Artificial Intelligence different from Human Intelligence?” How is our making AI in our image different from the idea of God making us in their image?

The book includes a queer romance. Are you hopeful about love as we know it surviving an AI-based future?

I think romantic love, including queer romantic love, is a subset of a larger love that we’re going to have to reclaim and fight for if we’re going to survive as a species. We can’t save queer love and/or romance in isolation. It’s all or nothing.

Tell us something we wouldn’t expect about The Queer Book of Revelation?

This is a tough one. I’ve lived in the story for some time now — there are no surprises to me. But maybe I can say this: with the exception of time travel, every technology the book describes exists or is being developed today in some form.

The Queer Book of Revelation, published by NB Publishers, will be launched at the Open Book Festival in Cape Town (6 -8- September), and at Exclusive Books Rosebank in Johannesburg on 10 September. Keep an eye out for it in leading bookstores and online retailers.

Leave a Reply