Queer life in Africa is also full of joy – remembering the carnival in Mozambique

A queer performer in Mozambique today. Courtesy Aghi/Outros Corpos Nossos

In late colonial Mozambique, in the city of Lourenço Marques (today’s Maputo), a carnival festival was held almost every year. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the event was more than just a street parade. It also became a space of queer expression and joy.

As a Brazilian queer scholar based in South Africa, I have been painfully aware that English-speaking contexts tend to be far better represented in queer African studies. I have chosen to focus on countries whose queer politics and history are lesser known and under-studied – such as Mozambique and Angola.

Which is how I came across the history of carnival celebrations in Lourenço Marques. With the support of Johannesburg’s Gala Queer Archive and LGBTIQ+ organisations such as the Arquivo de Identidade Angolano in Angola and Lambda in Mozambique, I’ve been collecting queer histories in and from these countries.

In these documentary projects, I strive to balance the focus on “African homophobia” by finding histories and spaces in which queer African cultures have also flourished (and, at times, continue to flourish).

In a recent research paper, I flesh out how the Mozambique festival opened up a space of freedom to the marginalised. Especially women of colour and queer people, black and white. It also built on and activated transnational networks in the wider Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) world. Brazilian musicians and cross-dressing performers, for example, travelled across borders to become important presences in late colonial African society.

Celebrating these histories of joy is important because it allows the archive to become a site of freedom too, where one might reclaim the past and imagine a brighter future.

Carnival as queer culture

Like others elsewhere in the world, the carnival festival in Lourenço Marques was a period of temporary subversion of dominant morals and social hierarchies of race, class, gender and sexuality. While the festivity had been celebrated in Mozambique since at least the 1900s, it went through a renewal in the late colonial period.

From the 1950s until the early 1970s, the carnival took place in unequal worlds. It was in the racially segregated spaces of elite clubs and hotels, on the one hand, and in the most popular and racially mixed environments of the subúrbios (suburbs), on the other. These middle- and low-income neighbourhoods, such as Mafalala, Alto Maé, Xipamanine and Malhangalene, were known hotspots of African culture and creativity.

Transnational connections shaped the celebrations too. Carnival parties often featured Brazilian musicians and rhythms, especially samba. Mozambican playwright Manoela Soeiro suggests that dancing samba and enjoying the Brazilian-style carnival offered black Mozambicans a kind of joy that was otherwise denied to them by dominant colonial culture.

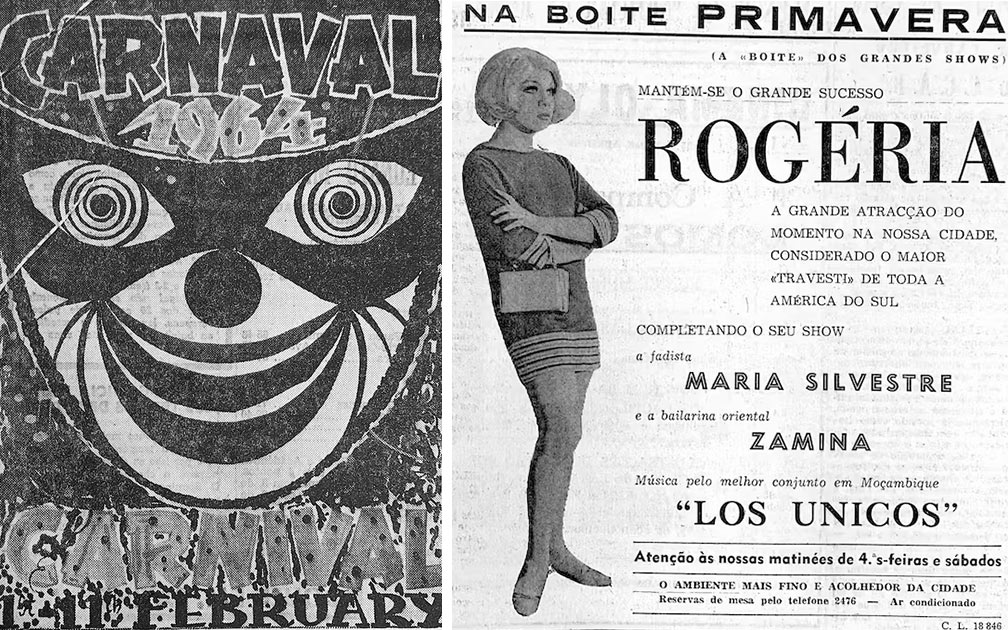

Besides Brazilian musicians, Lourenço Marques also received travestis, cross-dressing queer performers. Travestis were becoming increasingly successful in entertainment culture in Brazil and elsewhere, in theatre and film and nightlife. Brazilian travestis, such as the iconic Rogéria, held artistic residencies in Mozambique in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In Lourenço Marques and Beira, they performed regularly in clubs and cabarets, helping spur an emerging queer subculture.

Image 1: Carnival poster (Noticias) Image 2: Newspaper advertisement for a Rogéria performance (Notícias da Beira)

The Mozambique-born Portuguese writer Eduardo Pitta explains that their presence was a sign of cultural change. It signalled a relative openness on matters of gender and sexuality that reflected the global sexual revolution of the late 1960s.

These emerging urban and youth cultures pushed against the sexual and moral conservatism of the Portuguese colonial regime. Especially during the carnival. While travesti performances were secluded in clubs attended by a mostly white and middle-class clientele, popular forms of cross-dressing were common in the carnival.

A poem published in the Mozambique press in 1958 encouraged the practice as an expression of freedom:

Let go of the sorrows consuming you/ do what you feel like/ if you are a woman, wear a male mask/ do not mind being transformed/ if you are man, make yourself into a woman.

João, a working-class black Mozambican, described to me his experience of joining the street festivities dressed as a woman, even “wearing breasts”.

João mentioned his desire to experiment with femininity as a child, which he had never done for fear of outing himself. What was particularly compelling about the carnival, he said, was the ability to enjoy this freedom without social repercussions. Stories like this suggest that in Lourenço Marques the carnival could be a site of queer joy, however fleeting.

In the aftermath of independence, the ruling party Frelimo cancelled the street carnival. The socialist regime intended to build a new revolutionary culture by fighting practices associated with colonial society, including drinking and sexual licentiousness. It is not surprising that the carnival was caught up on this moralist wave. While the festival experienced a rebirth in the late 1980s, it never regained the status it once had.

Remembering queer joy

In gender and sexuality studies, much has been written about how desires are regulated and how gender stereotypes are produced over time. Looking at the carnival invites us to focus instead on moments of sexual transgression and gender-bending, to imagine the possibility of freedom and disruption, despite the inherent violence of the colonial situation and its aftermath.

In 2015, after 40 years of independence, Mozambique joined the growing list of countries to put an end to colonial era “anti-sodomy” laws. Despite this legal landmark and the country’s relative tolerance towards LGBTIQ+ people, a recent report suggests that Mozambique still needs to more effectively fight discrimination and violence against sexual and gender minorities.

Spaces of queer self-expression and joy exist more visibly now, but they have also flourished in the not so distant past. In remembering the carnival, we are invited to bring joy back to the centre of our collective memory. Not for the sake of history writing alone, but also to undertake the transformative labour of queer liberation – as the queer icons and dancing queens in Mozambique remind us.

This article, by Caio Simões de Araújo, Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape, is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Leave a Reply