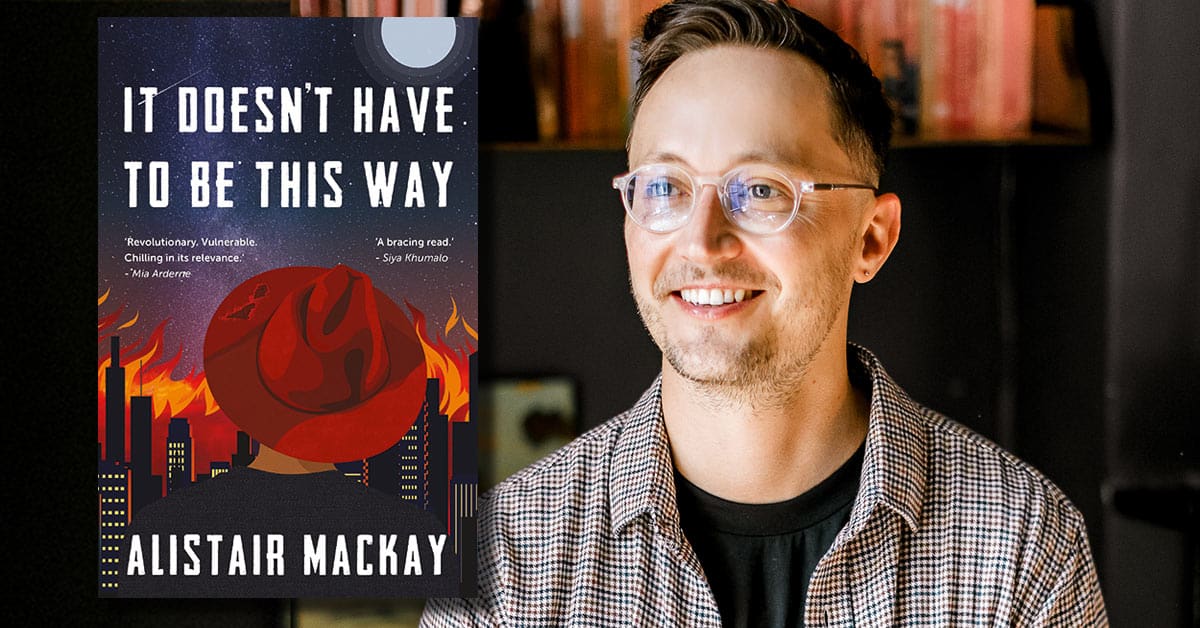

Queer Books | Alistair Mackay on his dazzling debut novel

It’s not every day that we see a South African, queer, dystopian-sci-fi novel hitting bookstore shelves. The fact that it’s also a gripping, poignant and timely book is further cause for celebration.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way is Alistair Mackay’s first novel, and it’s making waves in the literary world; earning him rave reviews.

Set in Cape Town, it’s the story of three queer men who face the unravelling of the world in a cataclysmic climatic collapse. Luthando’s environmental activism leads him to a clash with the government, while his life partner, Viwe, becomes embroiled in religious end-of-days fanaticism. And their friend Malcolm is worried that his work in the technological augmentation of human memory is being used for sinister purposes.

Mackay, who previously wrote for MambaOnline, has had his short stories published in journals and the anthologies Queer Africa and Queer Africa II. He holds an MA in Politics from Edinburgh University and an MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia University. Raised in Joburg, he now lives in Cape Town.

We spoke to Mackay about his debut “cli-fi” novel, what makes a queer book queer and how his passion for writing evolved.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way has been really well received. Were you expecting this kind of response?

It’s weird. I don’t think I allowed myself to expect anything. I was so focused on getting the book finished, on getting it to say what I wanted it to say, and then getting it published, that I didn’t really engage with how people would feel about it. There was this moment, when I first held a physical copy of it in my hands, when it suddenly hit me that people were going to read this thing – and I almost had a panic attack! I poured so much of myself into this book, and parts of it are very raw and vulnerable, and I think to be able to do that, I couldn’t dwell on what it would feel like for the work to be out in the public domain, waiting for people to judge it. It’s a leap of faith up to that point – believing you have something worth saying – and I get very nervous when I publish. I stress about whether people will like it. I need a lot of affirmation. So, I couldn’t allow myself to fixate on the public response before I was finished, or I wouldn’t have been able to finish writing. Obviously, I’m delighted with how the book has been received. I’ve been blown away by the support. I feel loved and relieved, but I’m also so happy to see that people are hungry for stories from Africa, stories with queer protagonists. There’s an appetite for new voices and new perspectives. It’s an exciting time for literature.

Where does your passion for writing come from? Can you trace it to a time in your life?

I think I’ve always enjoyed writing. My mom still has an illustrated story that I wrote when I was five or six – The Advenchas of The HYOOOJ See Dragin (My spelling has since improved). Like a lot of gay guys, I had a very unhappy period in my tweens and early teens. I hadn’t come out yet, my parents’ divorce had messed me up, and then I was sent to one of those toxic boarding schools that are supposed to “make men out of you”. There was hazing and bullying and being gay was about the lowest thing you could be. I think I retreated into myself. I wrote some terrible teenage poetry. There was this huge disconnect between my inner world and my life, and writing helped me to navigate that – and to make sense of my feelings. I still find writing helps me process my feelings and figure out what I really think about something. I also think it’s maybe an attempt to stand up against the world. To show what’s wrong with a situation, or make people laugh or help people to see things differently. I used to write a column for MambaOnline, which I loved. Exploring queer life and dating through an often-humorous lens. More recently, I’ve been drawn to writing fiction because I love the power fiction has over our emotions – I think stories can really transport readers, let them feel what it’s like to live someone else’s experience, or feel less lonely in their own experience. It’s a beautiful way of building empathy and connection.

Your book has been described as a sci-fi novel. Do you agree? What genre would you categorise it as?

It’s a little bit of everything! Genre-queer? There are definitely aspects of it that are science-fiction – It’s set over a period of fifteen years from today into the future, and the technology in it becomes increasingly frightening and invasive as the years go on. Embedded biotech. Mental software. Implants that allow people to distract themselves with constant virtual reality and content streaming and social media. But where a lot of traditional science fiction glorifies colonialism – expanding across the universe, settling on other planets – I wanted to subvert this idea and say maybe we can’t just escape the problems we’ve created by leaving, and maybe technological advancement isn’t always a good thing that will save us. In counterpoint to the science fiction elements, there is also a kind of magical realism running through the book. I try to encapsulate some of the magic and spirituality of nature, how calming it can be for mental health, to hint at everything we are losing, and also as a nod to indigenous wisdom and peoples. The book is so many other things too. It’s a dystopian novel, and it’s a climate change novel (there’s even a name for those now: cli-fi). And it’s a queer love story, and a book about friendship and chosen family and how we build community and support structures as queer people. I don’t think book retailers know where to put it! It’s sometimes in African Fiction, and sometimes in New Fiction, and a friend told me he found it in the History section of his local bookshop – which is maybe the one genre that it definitely isn’t.

Is ‘genre’ writing something you’ve always been attracted to?

It is, but not exclusively. I like the term ‘speculative fiction’, which encompasses sci-fi, magical realism, fable – the stories where there’s maybe something just a bit off, or a bit different about the world. I read a lot of “proper” sci-fi growing up, the kind with interstellar travel and that kind of thing, and I’m the youngest of three boys and both my older brothers adored Star Wars and had it playing basically on repeat on weekends, but I think these days I’m more attracted to the kind of speculative fiction that takes place on earth, that imagines alternative social structures or gender norms or histories / futures. Margaret Atwood, Shirley Jackson, Carmen Maria Machado. I like working in this genre, and I may well write another novel in it, but I don’t see myself as “a science fiction writer” at all. My next novel isn’t sci-fi. It’s plain old realism, set in Cape Town in 2018. Depending on how long it takes me, maybe that one can go in the History section.

It’s been said that sci-fi is rarely about the future but is a less obvious way of reflecting on or addressing the issues of the day.

Absolutely. I think a lot of sci-fi is a kind of reckoning with the pressing social issues of the day. Either through metaphor, or issues are extrapolated into the future, or they are exaggerated in some way so that they are clearer to see. In It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way, I’ve extrapolated our apathy and indifference about climate change into the future, and imagined what the world might look like if we continue to bury our heads in the sand and conduct business as usual. All of the most terrifying aspects of my book – such as a resurgent right-wing, rising inequality, climate instability and addictive tech – are already happening. People already live in conditions like this. I wanted to show what it feels like a little further down the road that we’re already on. To say, this is where we’re headed – do you like where we end up?

Why did you choose to set the book in Cape Town?

I lived overseas for a few years, and when I moved back it struck me with fresh force how dystopian our levels of inequality are. Cape Town is famous for its beauty, and it is very beautiful, but so many of its residents live in conditions that wealthy residents would consider hell on earth, but those parts are kept out of view, and out of the public imagination. And the situation is normalised. That’s something I wanted to explore in the book: the blindness of privilege, the idea that in many ways people are already living in a dystopia, but we only think of it as dystopian if these things happen to “us” rather than “them”. There’s that William Gibson quote that the “future is already here, it’s just unevenly distributed” and I think that is so starkly apparent in countries like South Africa, where some people have access to the newest, most impressive “future”, and others are living through the dark side of this relentless “progress”, such as the unemployment that could come from increased automation and AI etc. Cape Town’s also the perfect setting for a climate change novel because the effects of climate change are so dramatic here, and are already being felt. We’ve recently had the Day Zero drought, the peninsula gets ravaged by wildfires, and it’s a coastal city so parts of it will become flooded as the oceans rise.

Would you say that your novel is queer one?

It’s definitely a queer novel. The three main characters are all queer men, and that was important to me when writing it. I think queer lives and perspectives are still underrepresented in literature and art, and I wanted to do my little bit to fix that. On the one hand, to show queer love and queer sex and to tell a beautiful story of men who love each other, and on the other hand, to expose some of the trauma that many queer people are subjected to. One of the three main storylines grapples with issues that are particular to the queer experience – homophobia, and the self-loathing and shame that come from being surrounded by bigotry and judgement from a young age. I wanted to write this novel from a queer perspective for a few reasons. The most basic one is that I’m queer and I think queer narratives are important – for representation and to normalise our experiences. Why can’t a particular scenario be told from a queer perspective? But I also I wanted to imagine this future scenario of climate collapse from the viewpoint of marginalised people, because I think often when things get scary, society swings to the right. Conservatives make everything seem “safe” and predictable again by targeting those who are already marginalised. We see it with African immigrants in South Africa. We see it with the Supreme Court in the US threatening to reverse reproductive rights for women. And lastly, I wanted to tell a queer story because queer people are an inspiration. Our ability to love one another against all odds, often in the context of hatred, is a revolutionary act. It’s damn brave. And we have been coming up with alternatives to mainstream life for a long time – alternative family structures, alternative types of relationships, new ways of engaging with parenthood and gender roles. The world desperately needs alternatives now. We need to be able to imagine a way out of this mess, and queer people are good at coming up with alternative ways of being.

Does a queer book have to be about queer issues, or can it simply be about characters that happen to be queer? Can we ever get away from the politics of our identities?

I think queer books can be about anything the writer wants to explore. I love that there are more and more queer perspectives and stories out there, and that frees up writers (and readers) to choose the kinds of stories they want. Personally, I think both are important: stories about “queer issues” and stories where the queerness of the characters is incidental. I think it can help us feel less isolated and lonely to read about experiences that we have struggled with, but it’s also good sometimes to see characters just living their lives, without all the hang-ups of queer issues. Two of my favourite books are Less by Andrew Sean Greer, where the narrator is a gay author going through a midlife crisis, that’s funny and light and warm and romantic, and A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara, where she explores in unrelenting detail the trauma, shame and self-loathing of a queer man. We all contain multitudes, after all! I do think stories about queer people are always inherently political, because we live in a straight world that is hostile to us – sometimes overtly, violently hostile and sometimes just subtly, unintentionally hostile – and so choosing to live as ourselves is a political act. It can recede into the background in certain stories and situations, where the conflict with society is minimal, but I don’t think it ever goes away.

We’re living in a world on the brink of catastrophic climate and environmental collapse, yet it’s largely business as usual. Do you think your novel and other works (be they written or visual) can make a difference? Did that play a role in writing It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way?

I really hope so, because the climate science is clear and very, very bleak. If we don’t transition away from fossil fuels rapidly and urgently, we are truly screwed. And not in the fun way. A large part of why I wanted to write this book was as a kind of warning. It’s already too late to stop climate change, but it’s not too late to ensure it’s moderate enough for humanity to survive it. The problem is those in power – in government and in business – have vested interests in the existing economy, and are reluctant to change course as quickly as we require, so we need ground-up movements. I think we need the creative arts to help us imagine a way out of this mess, to put forward alternative paths and show people see what’s really going on. Ursula Le Guin said the world needs writers “who can see alternatives to how we live now, and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies, to other ways of being.” I hope movies like Don’t Look Up, and books like mine will make people stop and think, re-evaluate their choices, and maybe do something different. The trick is to get the balance right – scare people a little to shake them out of complacency, but don’t overwhelm them to the point where they feel hopeless or stripped of agency. We still need hope. There is still hope for us, and there is hope in my book, but it will disappear if there isn’t a concerted collective effort to change course.

What was your biggest challenge in seeing your first novel from conception through to release? The writing itself or the publishing process?

The writing! I really struggled with this book. I was obsessed with it, and couldn’t let it go, but it took me so long to get it right. It must have gone through at least four complete rewrites – where the structure changed and characters disappeared and storylines dropped out or emerged – and multiple drafts. It finally clicked into place for me when I stopped trying to control everything. When I let the characters dictate to me what they needed to do – and sometimes it wasn’t at all what I wanted for them. I didn’t set out to put them through so much! Sometimes I couldn’t believe what started happening in the story. The violence and the tenderness. When Viwe and Luthando, two of three main characters, have sex again for the first time in years and after a traumatic experience, Luthando starts to cry – and I got so emotional writing that scene. I could see it happening, but I didn’t know why he was crying. Is he relieved and feeling safe, or is he letting go of his grief? Viwe doesn’t understand what’s going on in Luthando’s head, either. Both of us are in the dark. I found the publishing process quite calming, actually. It took longer than I was expecting, but aside from that, it was wonderful to have another set of eyes on the book. Other people who were invested in it, and wanted it to succeed. It broke the obsessive spin of it all being in my own head.

Any advice to an aspirant queer author?

Sure. It sounds masochistic, but I think the most important thing is to write the stuff that makes you emotionally raw. What makes your perspective interesting and unique as a writer is often what you’ve been through, or the issues that you just can’t resolve in your own life. Figure out why you want to write, and then have the courage to delve deep into it. It doesn’t have to be bleak. Sometimes the end result can be really funny, but I think the work that resonates with people is raw and vulnerable. I would also suggest making time for writing every day. You can’t sit around waiting for inspiration. Inspiration is fickle, and it comes more regularly when you’re writing all the time. Take notes. Pay attention to the world around you. And lastly, be sure to get out of your head sometimes. Visit friends. Go for walks. Writing can be tough on your mental health, so make use of whatever social support you have. Have fun – both on the page and in life.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way is available in leading bookstores and as a Kindle edition.

We’re giving away two copies of It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way, courtesy of Kwela Books. To stand in line to win, email info@mambaonline.com with the answer to the question: In which city is It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way set?

Sounds like a compelling read!

Cape Town