Imraan Vagar on why it took him “so long” to come out

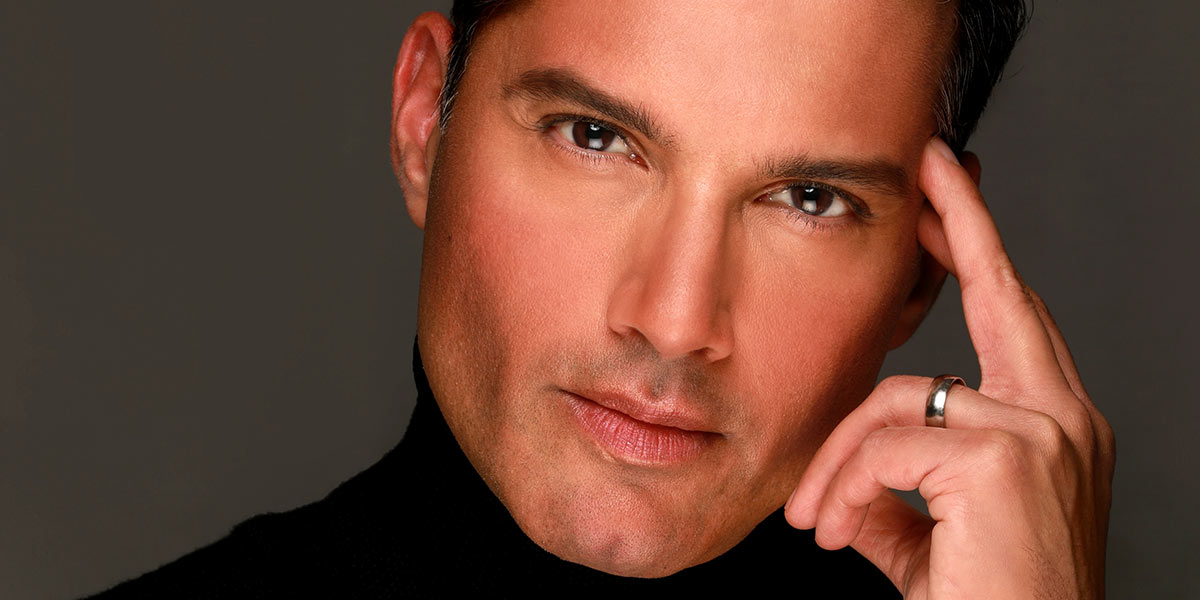

Imraan Vagar

The LGBTQ community puts immense pressure on queer celebrities and public figures to make a spectacular public announcement about their identity. If they don’t, we are quick to accuse them of being cowardly and not taking their platform to improve LGBTQ visibility seriously.

After all, as a traditionally invisible and persecuted community, the importance of role models cannot be underestimated. But we often forget that celebrities are also human beings, just like the rest of us – who are entitled to come out, or not, as they see fit.

Television personality Imraan Vagar has now revealed why he refused to publicly state that he is gay for such a long time. Best known as the former host of Eastern Mosaic and Miss South Africa, he is now the co-producer and director of SABC’s Mela and the producer and director of Afrikaans food series Geure Uit Die Vallei.

Vagar, who came out publicly in 2019, recently decided to address the topic in a multi-part blog post, the first of which is titled WTF Took You So Long?

He prefaces his observations by making the point that he hadn’t really been in the closet since his early twenties and that he was often photographed with male partners and at LGBTQ events. Vagar jokes that there was no “dastardly elaborate master plan to conceal my sexuality from the public.” Despite this, many people apparently didn’t make the connection.

“So if my sexual preference has been a secret, it’s been hiding in plain sight of anyone with half-decent gaydar or a facility for deductive reasoning,” he wrote, adding that “what I hadn’t done was explicitly confirm it or issue a public statement announcing it to all and sundry.”

He explains that he was resentful about the idea that he needed to declare his sexuality to the public. “Heterosexual presenters don’t come out as straight, why should I be expected to make an unsolicited declaration about which gender does it for me? Who cares? And how or why is it even relevant to the work anyway?”

Vagar says that being a celebrity only made the matter more complicated because becoming a public figure meant losing his privacy. It also resulted in wariness about opening up to others, socially and romantically.

“So putting up a firewall around my superego and soul and jealously guarding my private space and relationships from the kind of invasive and dehumanising scrutiny, not to mention morbid curiosity, that people in the public eye are uniquely subjected to – was my way of maintaining sanity and balance.”

The entertainment business is also a ruthless one he adds. “It’s a high-stakes zero-sum game in which I quickly came to realise that the most sacred and intimate aspects of a person’s life are considered fair game to be weaponised or used as fodder by industry players and grifters who would act in self-interest or self-dealing.”

Putting an LGBTQ identity into the mix didn’t help matters. “They may have gotten somewhat better at it nowadays, but in the nineties and early noughties, members of the press and public were still fixated on lurid stereotypes of the past and had a sort of juvenile, voyeuristic fascination with the mechanics of what gay men in particular got up to behind closed doors.

The media’s default inclination and incentive were to sensationalise, objectify or sexualise LGBTQ+ people for ratings, not humanise them,” Vagar says.

While self-identifying as “a citizen of the world – and a child of Africa” he notes that his Indian heritage played a further complicating intersecting role in his public identity.

Not only was he often described as “that Indian guy” on TV “now imagine how further dehumanising, depersonalising and objectifying it would be to then be labelled as ‘that gay Indian guy from TV’ had I come out in a symbolic gesture back then? To have to endure the indignity of being corralled into yet another tiny box of namelessness and superficial identity for expedience?

“I invite you to let your imagination run wild and dream up what sort of hackneyed, worn-out clichés and degradation the mainstream (and eventually social) media circus would have sought to visit upon me as an openly gay Indian public figure all those years ago?” he asks.

Imraan Vagar and his partner Chris Smit

Today, Vagar is indeed very publicly out, proud and in a relationship with his partner of 14 years, Chris Smit, who hosts Geure Uit Die Vallei. They are godfathers to a young girl.

Vagar tells MambaOnline that coming out publicly didn’t make a huge difference to his daily life since he was already unapologetically out to those close to him. “I mean I’ve cut people, including family, out of my life simply for the ‘crime’ of not loving and accepting me for my gayness, but rather grudgingly in spite of it. Of course, I don’t recommend that take-no-prisoners approach to others, but that’s how I’m wired. Some things are just not negotiable. My sexuality and my right to boldly express and celebrate it is one of them.”

He nevertheless believes that it may have made a difference to others; the reason why he ultimately chose to come out to the wider world. “I became alarmed by just how many young South African gay and bi men of colour – Indians, in particular – were still internalising harmful patriarchal and homophobic propaganda in this age of supposed awareness or ‘wokeness’,” Vagar says.

“In some ways, I think my coming out so matter-of-factly – as a brown public figure – has given a lot of them ‘permission’ to question and reconsider their programming. Their thank you messages via the blog and social media have been heart-warming – and so I’m experiencing a sort of vicarious pleasure from their stories of transformation and growth.”

Leave a Reply