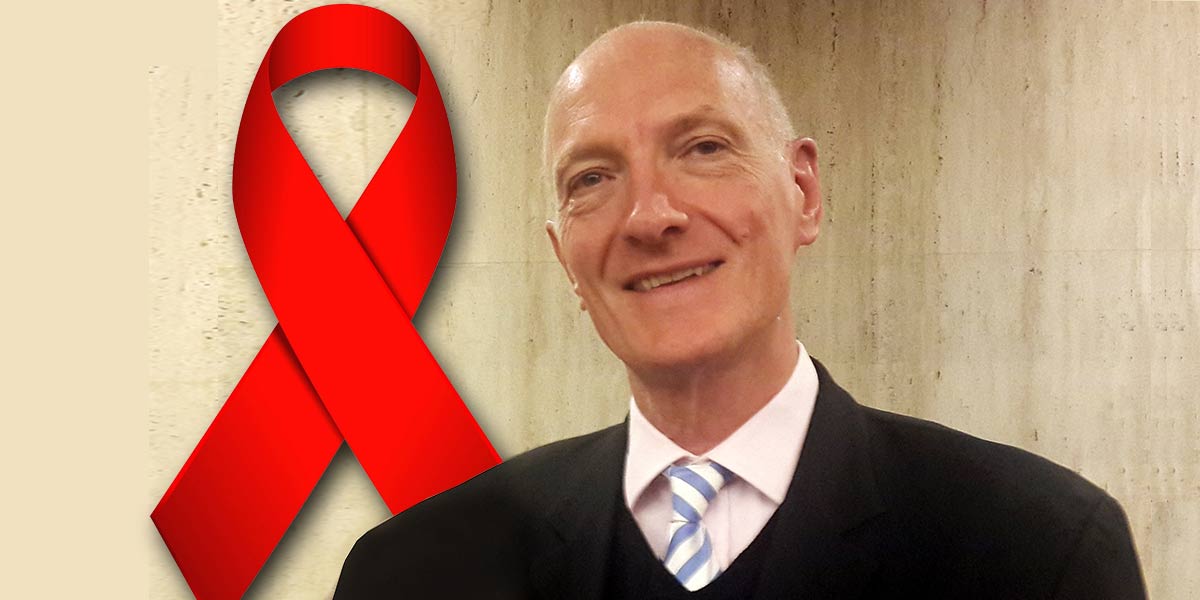

Edwin Cameron World AIDS Day Message 2019

Every year, now-retired Constitutional Court Justice Edwin Cameron pens a World AIDs Day message, published by Exit – SA’s longest-running LGBTQ publication – and shared by MambaOnline.

This is my fifteenth World AIDS Day message for EXIT newspaper. I mention this as a private landmark, because I value this newspaper (and its associated website, and MambaOnline, on which it is shared) as a crucial medium for getting out important messages on HIV and AIDS.

Every completed year is a landmark also for EXIT, which has been published since 1982. It was started in the dark days of apartheid, when men having sex with men (MSMs) were targeted and arrested and shamed and charged under stringent homophobic criminal prohibitions. That was when LGBTIs were treated as immoral, unbiblical, perverted criminals in South Africa. The apartheid government went so far as to set up a parliamentary committee, in 1987, to figure out even harsher prohibitions and punishments.

During that awful time, this newspaper served as a voice of pride and justice for the LGBTI community.

1982 was before we properly knew about AIDS. It was mostly just a rumour from America. We didn’t know, then, what was happening in Uganda. And we didn’t know how that same devastation would strike our own country.

1982 was before Simon Nkoli was arrested, in 1984. It was before the mass uprisings of the 1980s – which Simon helped instigate – forced the apartheid government to buckle.

And buckle apartheid did, in 1990. But the end of that era saw a new and frightening spectre: AIDS. We became a constitutional democracy just as a massive wave of HIV prevalence swept through our country.

That wave was totally unlike the shape and impact of HIV and AIDS in North America, Western Europe and Australasia.

There, HIV remained confined almost exclusively to gay men and MSMs. Those dying of AIDS were mostly white and generally middle-class. Men like me. I became infected with HIV at Easter 1985. I was diagnosed in December 1986. It was a death sentence, then, for me, and for hundreds of thousands of other gay men, mostly in North America and Europe.

But in Africa, the shape of the epidemic was very different. The disease’s pattern took an astonishingly different form. It was overwhelmingly a disease of black heterosexuals. Most of them, like the continent they lived in, were relatively poor. But black and white, rich and poor, African or non-African, we had one thing in common: AIDS was a death sentence for us all.

In our country, too, the heterosexual impact of AIDS dwarfed its effect on gay men and MSMs. The most important result was the ghastly debacle of President Mbeki’s AIDS denialism. For, with HIV, came also its most intimate, seemingly-inseparable travelling companions: stigma and shame.

It was shame about a mass sexually transmitted disease on the world’s only black continent that led President Mbeki to question the science and medicine of AIDS. It was shame that caused him to dispute the existence of the virus and to ask whether there was any point to HIV testing. And it was shame that, most catastrophically, caused him to deny our people anti-retroviral (ARV) treatment.

Presidential denialism hit our country just as Zackie Achmat’s Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), founded in the wake of Simon Nkoli’s tragic death from AIDS on 1 December 1998, achieved its biggest victory. The TAC triumphantly forced international drug companies to reduce the cost of ARVs, so that they could be provided to heterosexual black Africans as well as to gay North Americans and Europeans.

It was the TAC that confronted both the drug companies’ immoral profiteering and President Mbeki’s denialism. They took government to court, and won. The TAC case may yet be the Constitutional Court most significant judgment – one that ordered President Mbeki to start making ARVs available.

Today, South Africa has the world’s largest publicly-provided ARV treatment program. We owe it to enraged, brave, principled, strategically savvy, passionate activists. Not only to them, but also to our Constitution, and to the stout-hearted judges of the High Court and Constitutional Court (I was not yet a member) who granted the historic order against President Mbeki’s government.

Why these reflections for this World AIDS Day, 2019? Three reasons.

First, to know where we are, we must know where we come from. If we don’t know our history, we don’t know what we’ve achieved, and we don’t know what remains to be done, or how to do it. Memory is identity and pride and struggle. That is why South Africa’s Wits-based GALA – Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action – is uniquely important on our continent. It helps us understand who we are, by honouring those whose lives and identities history was determined to erase.

Second, the past is not yet past. It still lives with us. For most Africans, living on our beautiful continent, the terrors of homophobia continue every day. South Africa under apartheid is what life is like for LGBTIs in most of the rest of Africa. Police raids. Prosecutions. Street violence. Public hate speech. Homophobic murders.

Just last month, more than sixty Ugandans were rounded up and charged after a raid on a gay-friendly Kampala bar. In more than thirty countries in Africa, our love and our private adult enjoyments remain criminal.

Nigeria in 2013 enacted what is probably the worst homophobic law in human history. Under the law, to speak out for LGBTI dignity is defined – absurdly – as propagating gay marriage. And that carries a fourteen-year sentence in a Nigerian jail.

And AIDS. The past is not yet past. The stigma that propelled Mbeki-ite denialism also still lives. It silences us. It shames us. It stands in the path of people being tested. It impedes those tested from starting treatment. And, most grievously, shame and stigma are part of the reason why many people fail to keep up their treatment.

A third reason for these reflections is more personal. This year is a year of reflective reassessment for me. In August this year, I retired from judicial service, on the 25th anniversary of the day President Mandela appointed me as an (acting) judge in August 1994. (My appointment became permanent on 1 January 1995.)

Another anniversary: this November, as I write these words, I reflect with gratitude on 22 years of life – full and vigorous life – on ARVs. I started ARVs in November 1997. I was deathly ill. My life expectancy was 30-36 months. I faced certain death, like millions of others on our continent. It seemed certain I would die somewhere in the second half of 2000.

Instead, I lived. Lived because of the privilege of treatment access and of good medical care. (Thank you, Dr David Johnson, now relocated to Steytlerville, where he continues the best traditions of his public service.)

For too many Africans with HIV, that past, of the struggle for treatment, the struggle against stigma, is also not yet past.

There remains too much to do. To fight stigma. To urge gay men and MSMs to have fun safely, joyfully, and proudly. Get tested. Start treatment right away if you test positive. And to fight stigma. Fight it by talking. By asking. Have you been tested? By normalising a condition that nearly 8 million South Africans have. A condition that, roughly guessing, maybe one-quarter, or maybe more, of all gay men and MSMs in our country have.

So, as EXIT celebrates the mere joy of survival, so do I, with gratitude after 22 years on treatment. And while my message has remained largely the same, year after year, this year it comes with especial intensity – intensity for the urgent work that remains for us to do, as gay men and MSMs, as LGBTI activists, as caring South Africans, men and women, gay and straight, black and white.

We know how to manage HIV. Medically, it is a relatively easy condition to manage. To treat successfully. The medicines work. They still the virus in the body. It creeps away and hides, lying dormant, for so long as you regularly take your pills. And it is impossible for someone on successfully maintained ARV treatment to pass on the virus. Undetectable means untransmittable (U=U).

Why, then, if treatment is so easy, are only 3.5 million South Africans on ARVs – when another four million of us who are living with HIV are not?

The barriers lie in health care inequalities and in failures of efficiency and distribution. And in ourselves. In the stigma and shame we continue to carry within us, and to inflict on others.

So, this year, let us celebrate this World AIDS Day with new purpose. Let us determine to cast off stigma and shame. Let us undertake to test regularly, to learn and speak about our special vulnerability to HIV as gay men and MSMs. And, most important, as we celebrate our pride in our gayness, let us love safely.

Leave a Reply