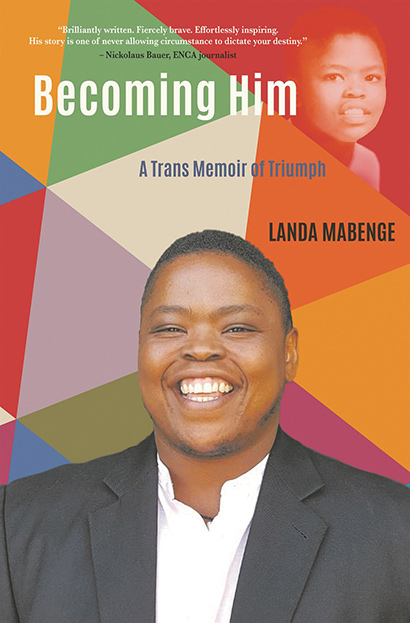

Landa Mabenge: Turning despair into triumph

Author, businessman and activist, Landa Mabenge is sharing his powerful story of overcoming rejection, ignorance and shame to create awareness about the challenges faced by transgender men.

Mabenge’s Becoming Him, a Trans Memoir of Triumph was published last year and has seen growing acclaim. It was recently selected by the KZN Department of Arts and Culture to be included in its libraries. It has also been nominated for the Sunday Times’ Alan Paton Award for non-fiction.

The book unflinchingly recounts Mabenge’s life as a trans mans, including horrific physical, emotional and psychological abuse in his youth. It goes on to depict his inspiring transition from hopelessness to the successful man he was meant to be.

Among his achievements was becoming the first transgender man to motivate a medical aid in South Africa to pay for his surgeries through the Groote Schuur Transgender Clinic.

The 28-year-old KZN-born groundbreaker is also receiving attention internationally. Last month he was selected from hundreds of applicants by America’s Human Rights Campaign (HRC) as one of its 2019 ‘Global Innovators’. Mabenge was one of 29 advocates from 27 countries who were invited to attend the HRC Foundation’s Global Summit in Washington, D.C.

Mabenge, who somehow finds time to run a firm that consults on transgender inclusion, spoke to MambaOnline about his successes.

Why did you decide to live your life so publicly as an openly transgender man?

Growing up I did not know what gender or sexuality meant. I had no idea why the boy I knew and felt myself to be did not make sense in a world that was identifying and socialising me as a girl. I had no language to express my truth or safe spaces to live my reality. When I could finally begin my journey towards becoming, there were no visible black South African transgender men who could serve as a compass for the beauty I presented. I could not find any literature or stories of hope that I could easily access in the public realm. And so, when I began living my truth, and had access to the resources and health interventions I needed, I realised that I had a duty to my fellow beings to tell my story. Whenever I think of all those who still have no access, no language and no resources, I realise the importance of continuing to live openly and publicly as a transgender man.

What drove you to write a book in particular?

The intention behind writing Becoming Him was two-fold. Firstly, to use my positive experiences as a black transgender man in South Africa to inspire hope, especially for those that are on their journey towards becoming. The second reason was to highlight the importance of dismantling the facade that masks the private despair most people have to endure whilst growing up. I felt it necessary to speak of the traumas and pains I had to endure growing up in a home with God-fearing, professional parents, whose selective actions left me damaged and wanting. I needed to speak of not being able to find a voice to speak my truth in spaces where I ought to have been safe.

How hard was it to recount some of the difficult experiences you had?

I found it very trying. There were days where I wanted to fold, as I feared the tentacles of the darkness I had worked so hard to liberate myself from, would web themselves deeper into the crevices of my heart and drive me back into the dark closet that is depression. During these times, I had to constantly remind myself of the Landa that is here to serve humanity. I had to remember that there was is a bigger goal in telling my story, and every time someone thanks me for Becoming Him I am happy I did not give up.

You have come through all this in one piece. What advice would you give to other trans folk who are still facing sometimes unbearable challenges?

It is beneficial to always remember that this is a journey; it has a lot of ups and downs, and at times can be extremely lonely and isolating. It is important to reach out to people and spaces that can provide some measure of support. There are a lot of organisations that are doing amazing work in the transgender space and have safe spaces where people can come together to chat and share strategies and more about their lives. Social media has made it possible for easier linkages and trans folk can use these to connect to these organisations and safe spaces and people. Most importantly, be kind and patient with the self and choose to be around people who see and receive you for the beauty you truly are.

You managed to get your medical aid to pay for your gender-realignment procedures. What was your argument to the medical aid and how difficult was it to get this approved?

This was one of the most arduous parts of my journey. Belonging to a medical aid is a condition of employment for many formally employed people in South Africa. In my case – as is the case with most transgender people – my medical aid did not work for me as my health care needs in terms of trans health are not seen as being medically necessary. I initially had a conversation with the clinical team at the Transgender Clinic at Groote Schuur and we decided that we would motivate for the payment of my surgeries. Our argument was pretty straightforward-being transgender is not a choice and Landa needs these surgeries to live a fulfilling life and to not merely exist. My initial medical aid did not bother to respond to my motivation. I then switched schemes to Bankmed as a spouse dependent on my then partner’s medical aid. After being rejected there as well I picked up the phone and demanded telephonic justification. I asked them to speak to my surgeon Kevin Adams. Their question to him was: “Does Landa really need these surgeries.” His response was simple: “These are the most important surgeries he will ever need in his life.”

Do you know if it has become more common for medical aids to do this now?

I don’t. What I do know is that if it was indeed common, there would be a lot less transgender people who still live with the ugly effects of dysphoria and mental health issues due to this reality being branded as not being medically necessary. A lot more work needs to be done in challenging the status quo.

Transgender men seem to be among the least visible members of the LGBTQ community. Why do you think that is?

I think its due to the fact that manhood comes with a lot of gate-keeping and thus unspoken expectations within society in general. While I can never conclusively speak on behalf of all transgender men, I can speak based on my experiences and what the journey into adult manhood has shown me. I think when a person reaches a point of near or full equilibrium in terms of their transmasculinity, there lingers an invisible expectation of how a ‘man’ ought to act and present in the world. A lot still hinges on ‘men’ leading in almost all spaces-another social behavioural construct. So I think it could be that the transgender men have gotten to a point where they just want to do them without any red tape or expectations as it were or, it could simply just be that they are not interested in presenting on public platforms. What I do know for certain though is that a lot of transgender men battle to get access to health resources in terms of aligning their bodies to their identity-and this is definitely also a key factor in terms of a lack of visibility.

What do you think is the significance of your book being selected by the KZN Department of Arts and Culture?

What do you think is the significance of your book being selected by the KZN Department of Arts and Culture?

I am grateful and believe it will go a long way towards expanding people’s minds and helping them to unlearn and relearn. I think it is important for such lived experiences to find their spaces in our country’s banks of knowledge expansion. I don’t see this as a win for Landa; it is a path towards greater awareness, towards educating society and ultimately, towards the removal of binaries in terms of gender and sexuality. KZN Arts and Culture prides itself on working towards a national identity that is reflective of South Africa’s democracy. I believe they are setting the wheels in motion and living this by including books like Becoming Him in their libraries.

You were recently selected to participate in the HRC’s annual Global Innovative Advocacy Summit. What was that like and what did you get from it?

This was an amazing opportunity for all 29 participants that were selected across the globe. Particularly amazing for me and the work that I do, in that, like the HRC, I am working towards inclusivity, particularly through the adoption of policies in universities and employment spaces through my independent consultancy, Landa Mabenge Consulting. I got to share best practices with global innovators from various countries, who face different and similar challenges as I do. One of the highlights for me was watching the movie, Rafiki, and thereafter engaging with the writer and director Wanuri Kahiu. This movie speaks about a forbidden love between two Kenyan women and serves as a reminder of the beauty of love in a world that is selective in terms of who has the liberty to love. I came back from the HRC Global Summit fired up to continue the work I do, to continue being of service and to continue striving towards gender and sexual diversity inclusion in all spaces I exist in.

Ultimately, what do you see as your life’s purpose?

My purpose in life is to teach, and the only way I can do this is to live an authentic life and use that life as a resource to educate.

what an incredible inspiration thank you