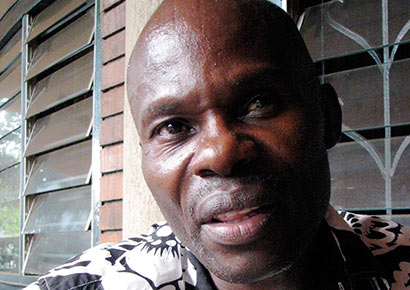

Will Uganda recognise slain LGBT activist David Kato as a hero?

Pic: Jocelyn Edwards

It is now seven years (on 26 January) since homophobes killed Ugandan gay hero David Kato in cold blood.

They murdered him just a few weeks after he won a court case against a tabloid newspaper in Uganda that had published the names of alleged homosexuals.

With David’s death, Uganda and its LGBTI community lost a great man. We will always remember him for bring to light the atrocities facing innocent LGBTI Ugandans.

Liberation from coups and dictators

On Friday, the same day we marked his death, others in Uganda were celebrating a very different anniversary. Because it also marked Uganda Liberation Day.

The east-African country left the British Empire back in 1962. But the period that followed was marred by political and military unrest, several coups, and a succession of rulers. In particular, the ruthless dictator Idi Amin, ruled the country throughout the 1970s.

And so, each year on 26 January, Uganda Liberation Day marks when the National Resistance Army overthrew the military junta. This brought in the reign of current President Yoweri Museveni.

He still presides over the annual celebration. And events this year included 200 Ugandans receiving medals for their contribution to the liberation of the country then and now.

Sadly, David Kato was not on that list. It seems the government is not keen to recognise LGBTI Ugandans.

This is inspite of the fact that Kato’s life was dedicated to liberating Uganda from one of the worst aspects of its colonial legacy.

Indeed, many of us LGBTI Ugandans believe David Kato would still be alive today if it wasn’t for the sodomy laws that Britain introduced to our country.

Uganda’s last gay king and its rich LGBTI tribal legacy

In fact, before the British came, Uganda had a positive gay history. One of the most loved Kings of Buganda, King Mwanga II, was homosexual with several boyfriends. He ruled in the late 19th century.

History also records that homosexuals existed in President Museveni’s tribe of Bahima in the Western part of Uganda. Same sex relationships were reported in central part of Uganda among the Banyoro and Baganda peoples. And Iteso societies in eastern Uganda accepted relationships between men who ‘behaved like women’.

Meanwhile, in the Northern part of Uganda among the Lango communities, they used the term ‘mukodo dako’ to refer to men who assumed another gender status. The Langos treated them as women and permitted them to marry other men.

British colonialists feared Uganda was too gay for them

But in the last years of gay King Mwanga II’s reign, the British were poised to shatter this history.

The British Empire was expanding and made Uganda a ‘protectorate’ in 1894. The British shipped in their own administrators to run the country.

These colonialists, of course, came from a United Kingdom that already criminalised and persecuted homosexuals. And they worried that Uganda’s tolerant atmosphere would somehow affect them.

Therefore the British colonial administrators and missionaries started a massive smear campaign against King Mwanga. They used scare tactics to warn he will infect other people, including British expatriates, with his homosexual behaviour.

With no respect for Uganda’s own history, they claimed Mwanga had learnt his gay behaviour from the Arabs.

And so, in 1902 they succeeded in introducing the country’s first known law against sodomy. It is this legislation that was incorporated into the country’s penal code in 1930. And it is effectively this penal code that still plagues us today.

The offence of having ‘carnal knowledge against the order of nature’, a term that did not exist in Uganda before, carried 14 years in prison and corporal punishment. Yes, the British weren’t satisfied with just jailing gay and bi men. They wanted to flog them too.

Later, in 1950, the authorities amended the code to remove corporal punishment. Sadly, by that point the poison had spread. The public now believed gay people deserved beatings, whatever the law said. It was this mob mentality that, arguably, cost David Kato his life – and many others too.

And ordinary Ugandans also adopted the idea that homosexuals are criminals. So there was no public outcry for the sodomy law to change when Uganda gained independence from the British in 1962.

LGBTI Ugandans are still victims of colonisation

We had gone from being a country where people accept and celebrate people to one where they stigmatise and criminalise LGBTIs.

Today, some Ugandans really believe that persecuting gay people is part of their culture. Perhaps it is even more absurd that Ugandans say the west is trying to push homosexuality on them. In fact, it is not homosexuality that is a western import, it’s homophobia.

Meanwhile, of course, the sodomy laws are still in Uganda’s penal code. Section 145,146 and 147 of the Uganda penal code, as introduced by the British, are so vague that the police are misusing them against innocent people.

I, myself, have had to flee the country in the face of this. Others continue to be victims. And our hero, David Kato, who did so much to fight this colonial legacy, paid the ultimate price when homophobes murdered him.

Even President Museveni admitted, while meeting with US human rights activists in 2013, that LGBTI people are part of Uganda’s history.

He accepted that, before the British came, homosexuals did not face persecution, killings or marginalisation.

Perhaps he could learn from his own country’s pre-colonial history. He could start by presenting David Kato with a posthumous medal next Uganda Liberation Day. After all, Kato is a true liberator.

Edwin Sesange is an African LGBTI rights advocate. This article first appeared on Gay Star News.

Leave a Reply