THANK YOU NELSON MANDELA

As the nation and the world mourn Nelson Mandela’s death, we remember some of the highlights of this icon’s relationship with the LGBTI community.

As the nation and the world mourn Nelson Mandela’s death, we remember some of the highlights of this icon’s relationship with the LGBTI community.

It is undoubtedly thanks to Mandela’s support for gay and lesbian equality at the dawn of our democracy, that we live in a country that constitutionally protects our rights – ensuring we are ALL free.

It is probable that the young Mandela was not always so inclined – but he would come to conclude later in life that no one can truly be free if anyone is excluded from that freedom.

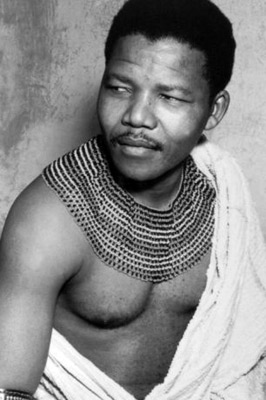

Born in rural Transkei on July 18, 1918, Rolihlahla Mandela, later named Nelson by a school teacher, is unlikely to have had much contact with concepts such as lesbian and gay identity.

When he was a student, and then a lawyer and freedom fighter in Johannesburg the times were not kind to gay people. The notion of LGBTI rights would have been considered absurd by most and few dared to be openly gay – especially as homosexuality was illegal.

Mandela joined the ANC in 1944, helping to form its Youth League. And it was through the ANC that he met a man who’s been credited with leading him to be become open to accepting gays and lesbians.

That man was Cecil Williams. This English born teacher, journalist and theatre director became an anti apartheid activist. He was a well known figure in Johannesburg high society but was also an underground revolutionary – and he was gay.

It’s not clear how open Williams was about his sexuality, but according to ANC freedom fighter and retired Constitutional Court Judge Albie Sachs, his comrades in the ANC knew that he was gay.

In a message of support for the 1990 Johannesburg Lesbian & Gay Pride March, Sachs wrote: “I think of the late Cecil Williams, a well-loved personality in the struggle in the 1940s and 1950s, whose homosexuality was well known to comrades, and I think how proud he would have been to be on this march.”

Williams and Mandela knew each other well and worked in various underground operations together. According to South African History Online “after the banning of the ANC and the formation of MK, Williams became involved in underground work of MK. For instance, when Mandela returned from military training in Addis Ababa, he was met by Williams in Bechuanaland (now Botswana).”

At times, Mandela, under the name of David Motsamayi, would pose as Williams’ chauffeur to avoid capture when he was being sought by the authorities. It was under these circumstances that Mandela, a fugitive, was finally arrested by the police.

On 5th August 1962, Williams and Mandela were stopped at roadblock near Howick in KwaZulu-Natal. In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela remembered Sergeant Vorster of the Pietermaritzburg police saying: “Ag, you’re Nelson Mandela, and this is Cecil Williams, and you are under arrest!”

That arrest led to a five year prison sentence for leaving the country illegally and inciting workers to strike. He was also tried for treason with nine others in the infamous Rivonia Trial.

Facing the death penalty, his famous ‘Speech from the Dock’ on 20 April 1964, reflected his inspiring values and vision:

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Mandela as a young man

Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island. After Mandela’s arrest, Williams was released and he returned to the UK where he died in 1979.

The story became an acclaimed 1999 documentary film, The Man Who Drove with Mandela, written and researched by Mark Gevisser.

Gevisser told the Mail & Guardian that Albie Sachs had said to him during his research: “If you want to understand why the older generation of ANC comrades are so receptive to the notion of gay equality in the constitutional debate, you need to go back and look at the role that Williams played.”

Sadly, and somewhat inexplicably, Williams is excluded from Mandela’s arrest scene in the film version of Long Walk to Freedom.

In the 1980s, while Mandela was imprisoned, the still-banned ANC was challenged to express an official position on gay and lesbian rights.

The now defunct Behind the Mask site quoted Mbeki as saying in 1986 that “the ANC is very firmly committed to removing all forms of discrimination and oppression in a liberated South Africa. That commitment must surely extend to the protection of gay rights.”

The late Simon Nkoli, who headed up the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW) was quoted as saying: “In 1987, the first statement came through Thabo Mbeki in London. His statement was quite positive of lesbian and gay people.”

By the time Mandela was released on Sunday 11 February 1990, the ANC appeared be open to the possibility of accepting the inclusion of sexual orientation protection in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

Nkoli said in an interview with the Green Left Weekly that he wrote an open letter to Mandela after his release asking him about his stance on gay and lesbian rights.

“He gave an assurance that gay and lesbian people are part of the oppressed in South Africa, and therefore there was no way he would reject them,” said Nkoli.

Mandela affirmed our right to constitutional protection, a world first, in one of his two inauguration speeches in Cape Town on 9 May 1994.

He said that he believed that South Africa could become “a constitutional, democratic, political order in which, regardless of colour, gender, religion, political opinion or sexual orientation, the law will provide for the equal protection of all citizens”.

In December 1994, Mandela appointed Edwin Cameron, an openly gay HIV positive man to the High Court and called him “One of South Africa’s new heroes”. Cameron went on to become a Constitutional Court judge.

“Mr Mandela was not only happy to appoint me – he did so with emphatic personal warmth, which he personally expressed to me and to others,” Justice Cameron wrote for Mambaonline earlier this year to mark Mandela’s birthday.

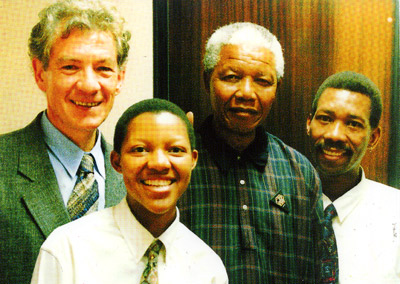

In 1995, Mandela again affirmed his support for the gay community by meeting with Nkoli and fellow LGBTI activist Phumi Mtetwa as well as openly gay British actor Sir Ian McKellen at Luthuli House in Johannesburg.

The struggle for equality for all came to fruition when President Nelson Mandela signed the final Constitution, and its groundbreaking Section Nine protection of people from unfair discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, into to law on 10 December 1996.

Nelson Mandela with LGBTI activist Sir Ian McKellen and LGBTI activists Phumi Mtetwa and Simon Nkoli (Source: Gala)

“Without President Mandela’s support that would have been unthinkable. His support made history for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people everywhere,” said Justice Cameron.

This constitutional equality led to the decriminalisation of homosexuality, full equality under the law and South Africa leading Africa and many other nations by legalising same-sex marriage.

Mandela’s understanding of human rights and equality as being inseparable from the rights of LGBTI people went on to make him an icon for gays and lesbians around the world.

This vision is encapsulated in one of Mandela’s famous quotes:

“I am not truly free if I am taking away someone else’s freedom, just as surely as I am not free when my freedom is taken from me. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity”

That quote was inscribed in a bronze plaque supporting same-sex marriage rights unveiled by the West Hollywood City Council in California in 2009.

That same year, a portrait of Nelson Mandela was included in an exhibition of Gay Icons at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Mandela’s powerful legacy will outlive us all. His vision of a world in which all people are universally equal and of immeasurable value will remain an inspiration and an ideal for LGBTI people for generations to come.

If we truly wish to honour this remarkable man we must each work to ensure that Mandela’s dream lives beyond the laws, words and examples he left us. That it becomes a reality for all those who remain victims of discrimination, hate and inequality. He would have wanted – and expected – no less.

Goodbye Tata. And thank you. We will not forget.

- Facebook Messenger

- Total200

Leave a Reply